National Museum Tour

2012 - 2015

- Installation Images - Introduction -

- Exhibition Facts - Illustrated Checklist -

- Essay from Collection Catalogue -

Installation at NCCU Art Museum, Durham, NC

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Exhibition Facts -Illustrated Checklist -

- Essay from Collection Catalogue -

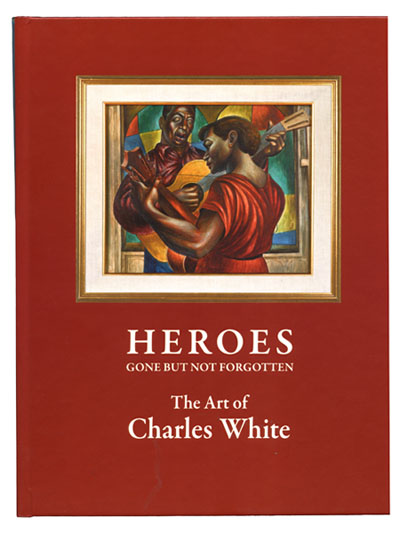

HEROES The Art of Charles White

Charles White 1977 Introduction HEROES: GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN, The Art of Charles White is a significant exhibition of forty-seven works—drawings, prints and paintings— that span the late 1930s through the 1970s. The works come from the collection of Arthur Primas, who has generously made them available as a national traveling museum exhibition. This large of a collection of White’s work has not been available to a wide museum audience for many decades. Many of his most revered works are featured in this collection, including “Gospel Singers,” “Head of Abraham Lincoln,” “J’Accuse #5,” “J’Accuse,” “Frederick Douglass” and works from the prestigious Johnson Publishing Company Collection spanning black history from slavery to Jubilee. This national touring museum exhibition HEROES: GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN begins with a presentation at the NCCU Art Museum in Durham, NC in the Fall of 2012. Charles White’s career spanned some five decades as both teacher and artist. His work embodies his philosophy, strength, resilience, tenderness, vulnerability, honesty, and his passionate love for the African American people. As one of America’s greatest visual critics in the realms of social justice and race relations, he enriched the lives of those who knew him and lived in his era, and those who appreciate his art now. Curator Charlotte Sherman of the Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles has been a champion of the work of Charles White for more than fifty years. The Heritage Gallery opened on La Cienega Boulevard in 1961 with the purpose of exhibiting artists that had been neglected in the exhibition scene on the west coast in the 1950s and ’60s. It was only in Europe that black artists, performers and writers experienced freedom. Civil rights marches moved throughout the United States. Social protest was in the air. Ben Horowitz brought New York artists from the “left” whose emphasis was Social Realism. Ed Biberman, one of the artists they represented, brought Charles to the gallery in the early 1960s. White’s work was already well known to both members of the Heritage Gallery and an exhibition was scheduled soon thereafter. Sherman and Horowitz developed a close working and personal relationship with White and over the years the Gallery had more than fifty exhibitions of his work. Charlotte Sherman is currently the Curator of the Arthur Primas Collection, which includes more than five hundred works of art by African American artists and artists of the Diaspora. The exhibition is organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA in association with the Heritage Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. A full color catalogue has been published to accompany the exhibition with essays by art historians and authors, Peter Clothier, former Dean of the Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, CA, and Will South, current Chief Curator for the Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, SC. |

Dates Available: 2012 onward Contents: 47 paintings, drawings, prints Space Req: 2000 sq feet. Loan Fee: Price on request Insurance: Exhibitor responsible Shipping: Exhibitor responsible Req: Appropriate security Contact: Jeffrey Landau -

2012 September 28 - December 31, 2012 2013 OPEN 2014 January 29 - May 23 June 7 - December 31 2015 OPEN

|

HEROES by Peter Clothier There are many different approaches to the work of a great artist. I’m choosing, for my present purpose, to think about Charles White’s work as a celebration of heroes. This is a word much debased in today’s common parlance. We hear it every day in the media: the patrol officer who helps a car crash victim from a burning vehicle is a hero, as is the firefighter who rescues a pet cat from a tree, or a private citizen who foils a robbery. My definition of a hero is the human being who overcomes real adversity and endures real suffering—a stand-in, in other words, for each one of us. I often think that every example of a man’s artwork is a portrait of himself, and Charles White was certainly a man who overcame significant adversity and endured suffering. He did so in three principal ways: as an African American born and raised on the south side of Chicago in the days before the great civil rights movement, when racism was still often violently rampant and went largely unquestioned; as a man who was challenged by severe health problems for much of his life; and as an artist persisting in the pursuit of a vision at odds with the powerful mainstream of post-World War II American art. His work was determinedly figurative when the mainstream went abstract; it concerned itself unrepentantly with social issues at a time when the most influential critics were busy championing the kind of art that referenced nothing but itself. From his schooldays, reading history books that notably omitted them, Charlie nurtured a passionate belief that black Americans needed heroes. (If I refer to him sometimes here as “Charlie,” it is not out of disrespect but because this is how I knew him: as a friend and stalwart ally at a moment of great adversity for the college—Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles County, as it was then called—where I was Dean and he the head of the drawing department, at a time when the school had lost its sole funding support from the county and faced at times the prospect of imminent closure. We shared a mutual trust and a mutual respect. And after we both left Otis, I started work on a book—with the aid of a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation—about this remarkable artist. Charlie worked throughout his distinguished career to provide a visual representation of black American heroes in the context of a culture that reactively dismissed or diminished black achievement. I came to understand this firsthand. My research provided me with a glimpse into the workings of the quietly insidious world of institutional racism. For any other (read “white”) artist of White’s stature, there would have been ample resources for a scholar to work with in libraries and museum archives. For an African American artist, however, I soon learned the results of casual neglect. Even at that time, in the 1970s, there was scant critical or historical information available; my only recourse was to delve into oral history, the memories of former friends, associates and colleagues scattered throughout the country. And I had the great privilege of spending many hours with the artist himself and his beloved wife, Fran, in their home high in the foothills of Altadena, California. For the last of those interviews, Charlie was hooked up to the oxygen tank that allowed him a few more weeks of life. He died, too young, at sixty-one years of age. It is important that I recall these events here because I need to disclose that Charlie White was a hero of my own, and that for this reason I am not a purely dispassionate observer. Heroism, as I understand it, is not some innate quality that simply manifests when the circumstance requires it—though courage, the quality at the heart of it, perhaps is. Heroes are created in the human imagination by the artful use of a medium for the benefit of the rest of us, who need our inspiration and the model they offer of exemplary behavior. Unlike the heroes of the ancient world or of traditional literature, Charles White’s are not drawn exclusively from great moments in history or from the world of temporal power, and certainly not from their elevated situation in life; their nobility is not of birth, but of hard work, achievement and the human spirit. But like those other, more conventional heroes, it is the artist’s vision that establishes their presence in our imaginative world. White’s medium was paint, or pen and ink, charcoal or graphite pencil. He developed his early skills as a child and a young man and, like all truly dedicated artists, spent an entire lifetime honing them. It is not surprising that the young Charles White, coming of age in the 1930s on the south side of Chicago, would first be influenced by the Social Realism of that period, nor by the socialist thought that prevailed amongst the intelligentsia and the creative minds of 1930s America. In the days immediately following the Great Depression, he did not have far to look to find evidence of the social and economic injustice that engaged progressive thinkers and working people of all kinds. It is not surprising, too, that his earliest ambitions gave voice to populist social messages in the form of large-scale wall paintings that emulated the example of the great Mexican painters—Rivera, Orozco, Siquieros—though there were models, too, closer at hand, in the murals by American artists sponsored by the Works Project Administration. The demand for social justice was in the air: White simply claimed it for his own heritage, in works now lost in all but photographic records: “Five Great American Negroes” and “A History of the Negro Press.” There are smaller works, however, by Charlie’s hand that manifest the stylistic conventions of the Social Realism that he first embraced. Aside from some atypical works of the period—we’ll return to them in a moment—the present collection includes just a few of them, notably the 1946 lithograph “Awaiting His Return” and the two 1948 offset lithographs “Head of a Man” and “Our War” from the magazine Negro: USA; also the slightly earlier (1946) ink on paper drawing “Freeport Columbia,” clearly made to be printed as an editorial commentary on the plight of returning African American GIs in the years following World War II—a time of truly heroic courage and sacrifice. The image speaks powerfully of the complacent conspiracy of politicians, police and Klansmen that condoned the practices of arson, pillage and lynching; and, in the figure of the insurrectional black soldier, the nascent, imminently looming spirit of power and hope acquired through suffering. It is important, at this point,to establish that the different values conventionally assigned to images intended for mass-market distribution—offset prints and lithographs—and original, handmade images like drawings and paintings are not especially useful when considering White’s contribution. As a young man particularly—but also later in life—he was passionate about the availability of his images and, particularly, of their message. More than anything, he wanted to be sure to share them with those he referred to always as “the folks”—people to whom he believed his message was important, even essential to the sense of pride needed for their social advancement. To ensure that his graphic images reached wide audiences, he was glad to put them out in the form of affordable portfolios or calendars, book or record album covers, or illustrations in left-wing magazines. Clearly, all of these early images reflect that reality. Equally clear are the stylistic influences that informed White’s earliest work—principally that of the Social Realism alluded to above, evident here in the relative scale of the figures, their heroic postures and expressions, the exaggeration of laborers’ hands and arms, and so on; and, in the squared-off quality of limbs and features, that of early twentieth-century European modernism, in particular Cubism, with which he was deeply impressed at the time of a 1940 Picasso exhibition in New Orleans during his brief resi-dence in that city. Yet already in early sketches—here we return to them—we find White warming up for what is soon to become a more naturalistic means to represent the figure. “Working Man” (c. 1938–1942) and “The Soldier” (1940) share something of the awkwardness of youthful experimentation with the line, but they are an important indication that the artist has something other in store—something more personal, spontaneous and lyrical—than the conventions of Social Realism. This is still more clear in the surprisingly early “Boy with Accordion” (1939), a charcoal drawing on paper that foreshadows what becomes White’s chief preoccupation in the early 1950s. Now resettled in New York, he throws himself into a great period of production, thriving socially in the company of a new circle of creative friends (Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier prominent amongst them) and in the start of his intense, liberating love affair with Fran. It is at this time that he leaves all but the fundamental lessons of Social Realism behind in favor of images where naturalistically-styled, volumetric portrayal blends with sketched, linear background information that gives context to the figure. In his personal passion for the African American musical traditions of gospel, soul and jazz, White finds around this time a more intimate means to put his artistic skills to work while still in the service of his unchanging goal to speak to others of the depth and richness of the black experience. The drawings that resulted appeared in such venues as record album covers, magazines and film credits. In the present collection, the painting “Gospel Singers” (1951)(see cover) best represents both the artist’s mood and his changing, now more lyrical style. His heroes now are artists of all kinds, those who bring their voices and their skills to the common cause of raising both consciousness and community pride. (Of special, somewhat different, but still notable interest is the remarkable portrait of Abraham Lincoln that dates from 1952—a hero, certainly, to African Americans for his achievement in emancipating blacks from slavery. It is noteworthy that this portrait is accomplished very much in the style of the German-born artist Winold Reiss, who was selected by the preeminent social critic and -advocate of black culture Alain Locke to provide illustrations for his seminal book, The New Negro, published in 1925. Locke’s book and Reiss’s portraits of the intelligentsia of the Harlem Renaissance were famously amongst White’s most profound early influences, and it is a pleasingly poignant irony that this, one of his only two white subjects, was executed in the manner of a white artist known for portraits of black Americans.) White’s strategy for establishing the “heroic” stature of his subjects in visual terms is evident in his two representations of “Micah” in the early 1960s—one woodcut and one lithograph. Micah is the biblical figure who spoke out against social injustice and promoted a world of equality and peace, a natural choice for White--, who stood for the same principles. His Micah is a towering, statuesque figure whose power is represented not only in the massive hands (a holdover, to be sure, from White’s Social Realist youth) but also in the posture, the folds of the robe, and the isolation of the figure from its background: the man stands alone. In each case, though, it is in the face that we find the expression of human suffering and the determination to endure and triumph over it, the quality of the hero that transcends pure physical strength. In the more naturalistic of the two works, the lithograph, the figure seems intent on moving forward, leading by example towards a more just and hopeful future. White takes a softer, gentler approach in the masterful charcoal drawings of the “J’Accuse” series of the mid-1960s, their title borrowed from the celebrated late-nineteenth century call for justice for the Jewish French army officer Alfred Dreyfus by the novelist Émile Zola. In #2 of the series, the multiple, beautifully modeled heads seem to merge with each other in a common cause against a background whose fiery energy fails to consume them, but rather lends them intensity and power. Each face perfectly reflects its own, individual struggle, and each manifests the sheer beauty boasted in the contemporaneous “Black Is Beautiful” movement. This image reads like the celebration of a celestial chorus, whose modulated harmonies and syncopations rise from darkness towards the light. “J’Accuse #6”—this is surely Belafonte?—manifests the same longing for salvation in song, this time in a single figure whose soulful inner energy reflects and rhymes with the creative turbulence around him. Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, White continues to refine his skills and further enrich his frames of reference. The “Wanted Poster” series and the historical portraits that follow them mark White’s return to painting—often now in much larger scale than earlier works—after a long period devoted, for health reasons, largely to graphic work. Here he works with a severely reduced and subdued palette, creating washes in mostly sepia tones that reflect period photography, and introduces the element of an abstract background that serves to evoke the long since folded parchment of an historical document. Ever alert to the ideas of contemporaries, White also begins to riff on the then current insistence on the concept, with the addition of verbal (and numerical) information to the visual experience of the artwork. His theme in the “Wanted Poster” series, of course, is the darkest stain on American history—the shameful heritage of slavery. But even in this context he chooses to highlight heroism rather than victimhood, the courage and resilience of those who risked escape, for whom the original wanted posters were put out. The artist plays with a rich irony: those “wanted” originally for recapture and punishment are “wanted” today for an entirely different reason—the inspiration of their heroic bid for freedom. In both examples of “Wanted Posters” included in this collection, White reminds his audience, with the date “19??,” that the battle is not yet won, that freedom shamefully to this day remains a mirage for too many of our fellow American citizens, and that the struggle continues. Contemporaneous with the “Wanted Poster” series, or shortly in their wake, came a number of comparable works that in their impressive scale as well as their technical mastery and seriousness of purpose must count amongst White’s most mature and authoritative accomplishments. They celebrate historical and cultural heroes from the days of slavery through the twentieth century: Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, the “Black Founding Fathers” Paul Cuffee and Richard Allen, the influential social historian W.E.B. Dubois and others. They further celebrate the contributions of the less well known, the anonymous “Black Worker,” as well as of black financiers and businessmen. They do this, each of them, in the context of the slave ancestors recalled by the recurring back-ground image of that folded document of indenture, acknow- ledging the debt to those who suffered in the early years. In “The Black Worker” (1974), this debt becomes explicit in the profile set eerily behind the capped head of this twentieth-century workman, whose haunted, if determined gaze looks out with quiet defiance into the world. If these works are White’s major contribution to the epic struggle for African American recognition and social equality, some of the latest works—“Love Letter lll” (1977), “Sound of Silence” (1978)—are amongst the most lyrical and self-assuredly serene of the artist’s entire opus. “I Have a Dream,” the lithograph commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for its groundbreaking 1976 exhibition, “Two Centuries of Black Art, 1750–1950,” takes its title from the historic speech of Dr. Martin Luther King that gave public voice to all the passion and energy of the surging civil rights movement. White’s image, though, is emotional on the intimate scale; alternatively titled “Madonna and Child,” it celebrates the heroic role of the black woman and mother in the struggle for freedom—a recurring theme in White’s work—and the hope represented by the child she tenderly carries in her arms. Head tilted heavenward, her lovely face highlighted and her eyes half-closed as if in prayer, she seems to offer her child to the future with a generosity of spirit and a purity of intention that invoke the freedom yet to be achieved. It may be that Charles White has yet to find his true place in American art history, as well as in the long and still unfinished story of the American journey towards equal rights for all. It was his life’s work, however, to reveal and honor the inherent, human beauty in faces that had too long remained “invisible”—to borrow from the lexicon of Ralph Ellison—and to recognize their role in the history of a country that only recently began to recognize the value of their contribution. In so doing, he bears witness not only to the heroism he finds in all his subjects, whether famous or obscure; he bears witness also to the best of humanity inherent in us all, and offers us the opportunity to contemplate that humanity in all its radiant beauty. Peter Clothier, 2012 Peter Clothier was Dean at Otis Art Institute during Charles White’s tenure there as Professor and Chair of the Drawing Department. In 1979, he received a Rockefeller Fellowship for a study of the artist’s work. He is the author of David Hockney in the Abbeville Modern Masters series and of scores of articles and reviews in national art journals. His most recent books are Persist: In Praise of the Creative Spirit in a World Gone Mad With Commerce (2010) and Mind Work (2011). © Peter Clothier, 2012

|